Ackermann function

In computability theory, the Ackermann function, named after Wilhelm Ackermann, is one of the simplest and earliest-discovered examples of a total computable function that is not primitive recursive. All primitive recursive functions are total and computable, but the Ackermann function illustrates that not all total computable functions are primitive recursive.

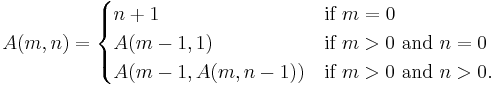

After Ackermann's publication[1] of his function (which had three nonnegative integer arguments), many authors modified it to suit various purposes, so that today "the Ackermann function" may refer to any of numerous variants of the original function. One common version, the two-argument Ackermann–Péter function, is defined as follows for nonnegative integers m and n:

Its value grows rapidly, even for small inputs. For example A(4,2) is an integer of 19,729 decimal digits.[2]

Contents |

History

In the late 1920s, the mathematicians Gabriel Sudan and Wilhelm Ackermann, students of David Hilbert, were studying the foundations of computation. Both Sudan and Ackermann are credited[3] with discovering total computable functions (termed simply "recursive" in some references) that are not primitive recursive. Sudan published the lesser-known Sudan function, then shortly afterwards and independently, in 1928, Ackermann published his function  . Ackermann's three-argument function,

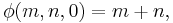

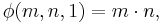

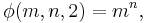

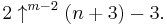

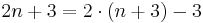

. Ackermann's three-argument function,  , is defined such that for p = 0, 1, 2, it reproduces the basic operations of addition, multiplication, and exponentiation as

, is defined such that for p = 0, 1, 2, it reproduces the basic operations of addition, multiplication, and exponentiation as

and for p > 2 it extends these basic operations in a way that happens to be expressible in Knuth's up-arrow notation as

.

.

(Aside from its historic role as a total-computable-but-not-primitive-recursive function, Ackermann's original function is seen to extend the basic arithmetic operations beyond exponentiation, although not as seamlessly as do variants of Ackermann's function that are specifically designed for that purpose — such as Goodstein's hyperoperation sequence.)

In On the Infinite, David Hilbert hypothesized that the Ackermann function was not primitive recursive, but it was Ackermann, Hilbert’s personal secretary and former student, who actually proved the hypothesis in his paper On Hilbert’s Construction of the Real Numbers. On the Infinite was Hilbert’s most important paper on the foundations of mathematics, serving as the heart of Hilbert's program to secure the foundation of transfinite numbers by basing them on finite methods.[1][4]

Rózsa Péter and Raphael Robinson later developed a two-variable version of the Ackermann function that became preferred by many authors.[5]

Definition and properties

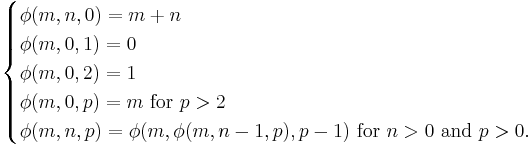

Ackermann's original three-argument function  is defined recursively as follows for nonnegative integers m, n, and p:

is defined recursively as follows for nonnegative integers m, n, and p:

Of the various two-argument versions, the one developed by Péter and Robinson (called "the" Ackermann function by some authors) is defined for nonnegative integers m and n as follows:

It may not be immediately obvious that the evaluation of  always terminates. However, the recursion is bounded because in each recursive application either m decreases, or m remains the same and n decreases. Each time that n reaches zero, m decreases, so m eventually reaches zero as well. (Expressed more technically, in each case the pair (m, n) decreases in the lexicographic order, which preserves the well-ordering of the non-negative integers.) However, when m decreases there is no upper bound on how much n can increase — and it will often increase greatly.

always terminates. However, the recursion is bounded because in each recursive application either m decreases, or m remains the same and n decreases. Each time that n reaches zero, m decreases, so m eventually reaches zero as well. (Expressed more technically, in each case the pair (m, n) decreases in the lexicographic order, which preserves the well-ordering of the non-negative integers.) However, when m decreases there is no upper bound on how much n can increase — and it will often increase greatly.

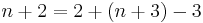

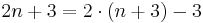

The Péter-Ackermann function can also be expressed in terms of various other versions of the Ackermann function:

- the indexed version of Knuth's up-arrow notation (extended to integer indices ≥ -2):

-

- A(m, n) =

- A(m, n) =

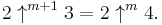

- The part of the definition A(m, 0) = A(m-1, 1) corresponds to

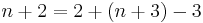

- hyper operators:

-

- A(m, n) = hyper(2, m, n + 3) − 3.

- Conway chained arrow notation:

-

- A(m, n) = (2 → (n+3) → (m − 2)) − 3 for m > 2

- hence

- 2 → n → m = A(m+2,n-3) + 3 for n>2.

- (n=1 and n=2 would correspond with A(m,−2) = −1 and A(m,−1) = 1, which could logically be added.)

For small values of m like 1, 2, or 3, the Ackermann function grows relatively slowly with respect to n (at most exponentially). For m ≥ 4, however, it grows much more quickly; even A(4, 2) is about 2×1019728, and the decimal expansion of A(4, 3) is very large by any typical measure.

If we define the function f (n) = A(n, n), which increases both m and n at the same time, we have a function of one variable that dwarfs every primitive recursive function, including very fast-growing functions such as the exponential function, the factorial function, multi- and superfactorial functions, and even functions defined using Knuth's up-arrow notation (except when the indexed up-arrow is used).

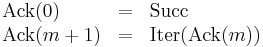

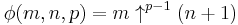

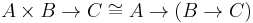

This extreme growth can be exploited to show that f, which is obviously computable on a machine with infinite memory such as a Turing machine and so is a computable function, grows faster than any primitive recursive function and is therefore not primitive recursive. In a category with exponentials, using the isomorphism  (in computer science, this is called currying), the Ackermann function may be defined via primitive recursion over higher-order functionals as follows:

(in computer science, this is called currying), the Ackermann function may be defined via primitive recursion over higher-order functionals as follows:

where Succ is the usual successor function and Iter is defined by primitive recursion as well:

One interesting aspect of the Ackermann function is that the only arithmetic operations it ever uses are addition and subtraction of 1. Its properties come solely from the power of unlimited recursion. This also implies that its running time is at least proportional to its output, and so is also extremely huge. In actuality, for most cases the running time is far larger than the output; see below.

Table of values

Computing the Ackermann function can be restated in terms of an infinite table. We place the natural numbers along the top row. To determine a number in the table, take the number immediately to the left, then look up the required number in the previous row, at the position given by the number just taken. If there is no number to its left, simply look at the column headed "1" in the previous row. Here is a small upper-left portion of the table:

| m\n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |  |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |  |

| 2 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 | 11 |  |

| 3 | 5 | 13 | 29 | 61 | 125 |  |

| 4 | 13 | 65533 | 265536 − 3 |  |

|

|

The numbers listed here in a recursive reference are very large and cannot be easily notated in some other form.

Despite the large values occurring in this early section of the table, some even larger numbers have been defined, such as Graham's number, which cannot be written with any small number of Knuth arrows. This number is constructed with a technique similar to applying the Ackermann function to itself recursively.

This is a repeat of the above table, but with the values replaced by the relevant expression from the function definition to show the pattern clearly:

| m\n | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0+1 | 1+1 | 2+1 | 3+1 | 4+1 |  |

| 1 | A(0,1) | A(0,A(1,0)) | A(0,A(1,1)) | A(0,A(1,2)) | A(0,A(1,3)) |  |

| 2 | A(1,1) | A(1,A(2,0)) | A(1,A(2,1)) | A(1,A(2,2)) | A(1,A(2,3)) |  |

| 3 | A(2,1) | A(2,A(3,0)) | A(2,A(3,1)) | A(2,A(3,2)) | A(2,A(3,3)) |  |

| 4 | A(3,1) | A(3,A(4,0)) | A(3,A(4,1)) | A(3,A(4,2)) | A(3,A(4,3)) |

|

| 5 | A(4,1) | A(4,A(5,0)) | A(4,A(5,1)) | A(4,A(5,2)) | A(4,A(5,3)) |

A(4, A(5, n-1)) |

| 6 | A(5,1) | A(5,A(6,0)) | A(5,A(6,1)) | A(5,A(6,2)) | A(5,A(6,3)) |

A(5, A(6, n-1)) |

Extension

The first three Ackermann functions can be expressed through elementary functions; they allow straightforward analytic extension for complex values of the second argument. In this sense, A(1,z), A(2,z), A(3,z) are analytic functions in the whole z-plane.

No such extension is yet established for A(m,z) at integer m>3. The sketch in the figure at right represents the possible realization of such extension, that remains limited at  . The drawing indicates that, perhaps, the extension of A(4,z), analytic in the whole z-plane, is not possible; the analytic extension should have a singularity at z=-5 and cut at the real axis for z < -5. Such cut and singularities seem to be typical also for the tetration function.

. The drawing indicates that, perhaps, the extension of A(4,z), analytic in the whole z-plane, is not possible; the analytic extension should have a singularity at z=-5 and cut at the real axis for z < -5. Such cut and singularities seem to be typical also for the tetration function.

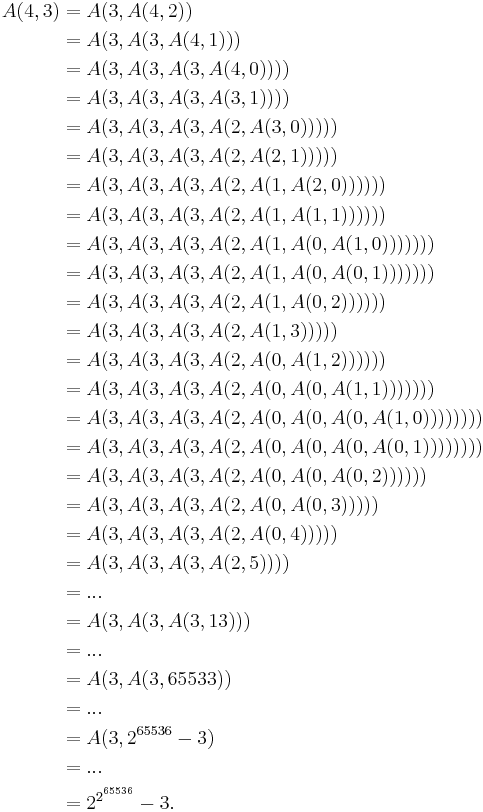

Expansion

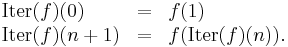

To see how the Ackermann function grows so quickly, it helps to expand out some simple expressions using the rules in the original definition. For example, we can fully evaluate  in the following way:

in the following way:

To demonstrate how  's computation results in many steps and in a large number:

's computation results in many steps and in a large number:

Written as a power of 10, this is roughly equivalent to 106.031×1019727.

Inverse

Since the function f (n) = A(n, n) considered above grows very rapidly, its inverse function, f−1, grows very slowly. This inverse Ackermann function f−1 is usually denoted by α. In fact, α(n) is less than 5 for any practical input size n, since A(4, 4) is on the order of  .

.

This inverse appears in the time complexity of some algorithms, such as the disjoint-set data structure and Chazelle's algorithm for minimum spanning trees. Sometimes Ackermann's original function or other variations are used in these settings, but they all grow at similarly high rates. In particular, some modified functions simplify the expression by eliminating the −3 and similar terms.

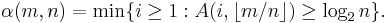

A two-parameter variation of the inverse Ackermann function can be defined as follows, where  is the floor function:

is the floor function:

This function arises in more precise analyses of the algorithms mentioned above, and gives a more refined time bound. In the disjoint-set data structure, m represents the number of operations while n represents the number of elements; in the minimum spanning tree algorithm, m represents the number of edges while n represents the number of vertices. Several slightly different definitions of α(m, n) exist; for example, log2 n is sometimes replaced by n, and the floor function is sometimes replaced by a ceiling.

Other studies might define an inverse function of one where m is set to a constant, such that the inverse applies to a particular row.[7]

Use as benchmark

The Ackermann function, due to its definition in terms of extremely deep recursion, can be used as a benchmark of a compiler's ability to optimize recursion. The first use of Ackermann's function in this way was by Yngve Sundblad, The Ackermann function. A Theoretical, computational and formula manipulative study. (BIT 11 (1971), 107119).

This seminal paper was taken up by Brian Wichmann (co-author of the Whetstone benchmark) in a trilogy of papers written between 1975 and 1982.[8][9][10]

For example, a compiler which, in analyzing the computation of A(3, 30), is able to save intermediate values like A(3, n) and A(2, n) in that calculation rather than recomputing them, can speed up computation of A(3, 30) by a factor of hundreds of thousands. Also, if A(2, n) is computed directly rather than as a recursive expansion of the form A(1, A(1, A(1,...A(1, 0)...))), this will save significant amounts of time. Computing A(1, n) takes linear time in n. Computing A(2, n) requires quadratic time, since it expands to O(n) nested calls to A(1, i) for various i. Computing A(3, n) requires time proportionate to 4n+1. The computation of A(3, 1) in the example above takes 16 (42) steps.

A(4, 2), which appears as a decimal expansion in several web pages, cannot possibly be computed by simple recursive application of the Ackermann function in any tractable amount of time. Instead, shortcut formulas such as A(3, n) = 8×2n−3 are used as an optimization to complete some of the recursive calls.

A practical method of computing functions similar to Ackermann's is to use memoization of intermediate results. A compiler could apply this technique to a function automatically using Donald Michie's "memo functions".[11]

Ackermann numbers

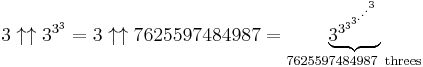

In The Book of Numbers, John Horton Conway and Richard K. Guy define the sequence of Ackermann numbers to be 1↑1, 2↑↑2, 3↑↑↑3, etc.[12]; that is, the nth Ackermann number is defined to be n↑nn (n = 1, 2, 3, ...), where m↑kn is Knuth's up-arrow version of the Ackermann function.

The first few Ackermann numbers are:

-

- 1↑1 = 11 = 1,

- 2↑↑2 = 2↑2 = 22 = 4,

- 3↑↑↑3 = 3↑↑3↑↑3 = 3↑↑(3↑3↑3) =

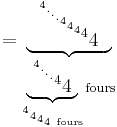

The fourth Ackermann number, 4↑↑↑↑4, can be written in terms of tetration towers as follows:

- 4↑↑↑↑4 = 4↑↑↑4↑↑↑4↑↑↑4 = 4↑↑↑4↑↑↑(4↑↑4↑↑4↑↑4)

-

Explanation: in the middle layer, there is a tower of tetration whose full height is  and the final result is the top layer of tetrated 4's whose full height equals the calculation of the middle layer. Note that by way of size comparison, the simple expression 44 already exceeds a googolplex, so the fourth Ackermann number is quite large.

and the final result is the top layer of tetrated 4's whose full height equals the calculation of the middle layer. Note that by way of size comparison, the simple expression 44 already exceeds a googolplex, so the fourth Ackermann number is quite large.

Alternatively, this can be written in terms of exponentiation towers as

- where the number of towers on the previous line (including the rightmost "4") is

- where the number of towers on the previous line (including the rightmost "4") is

where the number of "4"s in each tower, on each of the lines above, is specified by the value of the next tower to its right (as indicated by a brace).

See also

- Computability theory

- Recursion (computer science)

- Primitive recursive function

- Double recursion

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wilhelm Ackermann (1928). "Zum Hilbertschen Aufbau der reellen Zahlen". Mathematische Annalen 99: 118–133. doi:10.1007/BF01459088.

- ↑ Decimal expansion of A(4,2)

- ↑ Cristian Calude, Solomon Marcus and Ionel Tevy (November 1979). "The first example of a recursive function which is not primitive recursive". Historia Math. 6 (4): 380–84. doi:10.1016/0315-0860(79)90024-7.

- ↑ von Heijenoort. From Frege To Gödel, 1967.

- ↑ Raphael M. Robinson (1948). "Recursion and Double Recursion". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 54: 987–93. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1948-09121-2. http://projecteuclid.org/DPubS?verb=Display&version=1.0&service=UI&handle=euclid.bams/1183512393&page=record.

- ↑ Kouznetsov, D. "Ackermann functions of complex argument"

- ↑ An inverse-Ackermann style lower bound for the online minimum spanning tree verification problem November 2002

- ↑ "Ackermann's Function: A Study In The Efficiency Of Calling Procedures". 1975. http://history.dcs.ed.ac.uk/archive/docs/Imp_Benchmarks/ack.pdf.

- ↑ "How to Call Procedures, or Second Thoughts on Ackermann's Function". 1977. http://history.dcs.ed.ac.uk/archive/docs/Imp_Benchmarks/ackpe.pdf.

- ↑ "Latest results from the procedure calling test, Ackermann's function". 1982. http://history.dcs.ed.ac.uk/archive/docs/Imp_Benchmarks/acklt.pdf.

- ↑ Example: Explicit memo function version of Ackermann's function implemented in PL/SQL

- ↑ John Horton Conway and Richard K. Guy. The Book of Numbers. New York: Springer-Verlag, pp. 60-61, 1996. ISBN 038797993X

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Ackermann function" from MathWorld.

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document "Ackermann's function" by Paul E. Black (Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures).

This article incorporates public domain material from the NIST document "Ackermann's function" by Paul E. Black (Dictionary of Algorithms and Data Structures).- An animated Ackermann function calculator

- Scott Aaronson, Who can name the biggest number? (1999)

- Ackermann function's. Includes a table of some values.

- Hyper-operations: Ackermann's Function and New Arithmetical Operation

- Robert Munafo's Large Numbers describes several variations on the definition of A.

- Gabriel Nivasch, Inverse Ackermann without pain on the inverse Ackermann function.

- Raimund Seidel, Understanding the inverse Ackermann function (PDF presentation).

- The Ackermann function written in different programming languages, (on rosettacode.org)

- Ackermann's Function (Archived 2009-10-24) - some study and programming by Harry J. Smith